Porosity in Welding: What it Is, Causes & Remedies

Last Updated on

You’ve got your hood down. You’re welding a groove weld nice and smooth. Everything is looking consistent. You’re in the zone.

Then the weld puddle starts sputtering a little bit. You think, “It’s just some extra mill scale burning off of the edge of the plate. No big deal, right?” You continue welding. Then you lift up your hood to admire your work. You knock off the slag, anticipating the luster of a perfectly placed weld. But your heart sinks. You’ve got porosity.

Now you’re kicking yourself for not paying attention to the irregularities of the arc. What would have been an easy fix had you stopped welding when you noticed the sputtering is now going to take you an hour to fix. It’s easy to lay weld in a joint. But to take a bad weld out, that’s a whole different story.

Undercut, an occasional slag inclusion, or cold lap, these defects are bad enough. But they can be repaired without removing a whole lot of the original weld. But porosity is another story. If you have a lot of it, sometimes it requires moving the entire weld.

In short, porosity is where gases, most often oxygen or atmospheric gases, get trapped inside of the weld during cooling. This can occur for several reasons which we will cover in this article. We will also cover how to identify it and fix it.

Improper Gas Coverage

One of the most common causes of porosity is little to no gas coverage. Of course, this is assuming that you are using a welding process that utilizes shielding gas such as MIG or Dual Shield Flux-cored welding. The primary purpose of a shielding gas is to shield the weld pool from outside contaminants, including atmospheric gases that can get inside the weld. The shielding gas pushes the atmospheric gases away and protects the molten weld pool.

- What does it look like?

You will know that you have porosity from lack of gas coverage because you will have lots of pinholes throughout your weld. Sometimes many pinholes can be a problem with the quality of the base metal or the flux. However, if you grind into the weld and see deep pinholes, you know that you have no gas coverage.

- Remedy

Pretty much the entire weld will need to be repaired. It is far faster to carbon-arc gouge to remove the weld metal, but you can use a grinder as well. If your weld is larger than a 5/16” fillet, it’s going to take a long time to grind out the whole weld, especially if it is long.

Presence of Moisture

Moisture, as a major cause of porosity, is usually more of a problem when working outside in inclement weather. But a slightly damp piece of steel is not going to ruin your whole weld. The heat from the arc can usually dry that moisture right up without any major problems.\

- What does it look like?

If lack of gas coverage causes many pinholes in the weld, then the presence of moisture will make your weld look like swiss cheese. The trapped moisture can do severe damage to the weld overtime, including causing hydrogen cracking. Hydrogen cracking usually happens more when flux electrodes are stored improperly (they can collect moisture) and afterward are used to weld, thereby depositing hydrogen into the weld which when trapped, can cause embrittlement and weaken the material.

- Remedy

To fix this you need to carbon-arc gouge and/or grind all of the bad weld out before rewelding. But the prevention is much easier than repair. If you are working outside where there is excessive moisture, be sure to preheat your material with a rosebud (large tipped oxyfuel torch designed for preheating). The moisture will dry up. Be sure to ‘sweat’ the material throughout the potential heat-affected zone (HAZ). A good rule of thumb is to sweat it about one to two inches from the joint on both joint members.

Contaminated Surface

Not all the steel that you get comes perfectly clean. Often the case is that the supplier had it sitting outside in the yard collecting rainwater, bird droppings, grease, etc. When that piece of steel is cut and fit-up, you might assume that it’s ready to weld. After you weld, you notice a lot of irregular porosity.\

- What does it look like?

There is no rhyme or reason for this kind of porosity. Filthy steel will contaminate different parts of the weld differently. It can range from pinholes to large holes.

- Remedy

Ensure that the surface is spick and span before welding. Oftentimes the surface contamination is not due to dirt or grease, but it is in the material itself. In this case, grind off the mill scale until the metal shines. Just be sure to not grind into the base metal.

Too Long of an Arc

This often works in combination with poor gas coverage, especially if you are welding MIG or FCAW. If you are welding in a tough-to-reach spot, or you are welding a groove weld between thick plate where your welding gun cannot reach well, sometimes the only way to get the job done is to long-arc it.

- What does it look like?

Usually, this type of porosity will manifest as pinholes. But since you do have gas coverage, expect the porosity to be spotty and inconsistent.

- Remedy

Ensure that all breezes and drafts are prevented from reaching your weld. Put up weld screens, cardboard, plywood, or whatever you can find so that your shielding gas is effective. You can also turn up your shielding gas slightly. Alter your machine settings if you are able so that you can get a more consistent arc and slower travel speed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you weld over porosity?

In general, it is not a good idea to weld over porosity. If it runs deep, then it should be ground out and rewelded. However, there are instances where maybe the weld isn’t too critical and has a couple of pinholes. Most structural welding codes have an allowance for a certain number of pinholes for a specific length. It’s always good to check with the CWI (Certified Welding Inspector) to see if you can’t just trigger a couple of pinholes.

What causes wormhole porosity?

Wormhole porosity is a defect where there are indentations on the surface of the weld. This usually happens with FCAW when there is nitrogen trying to escape the weld as it is solidifying. The result is an elongated divot in the weld, often accompanied by pinholes. This is usually caused by surface contamination of the base metal. You may also be repairing a weldment that has already been painted. If you don’t grind off or burn off enough paint before welding, that paint will find its way into your weld and can cause wormhole porosity.

What is a crater hole in welding?

A crater hole can be classified as a type of porosity. This happens if you are welding a bead and taper off too quickly as you are finishing. The result is that the weld pool does not get filled in completely as the weld is being finished. Sometimes there is a small to a medium-sized hole in this crater. The solution to this is simple. As you are finishing the weld, hold the arc at your stopping point, drag it 1/8” to ¼” back over the weld, and return to the very end. This will help round out the ending point of your weld.

Final Thoughts

By understanding the causes of porosity in welding, you should know how to avoid most of it. If your machine is set right, you have enough gas coverage, and your material is clean, then you’ve already won half the battle. Just remember that is far more efficient (and less frustrating) to stop welding to check if it’s turning out alright than it is to have to grind out 16 inches of bad weld, especially if it’s in a tight spot. Knowing how a good weld feels can give you a baseline. This will help you judge if something “just doesn’t feel right.”

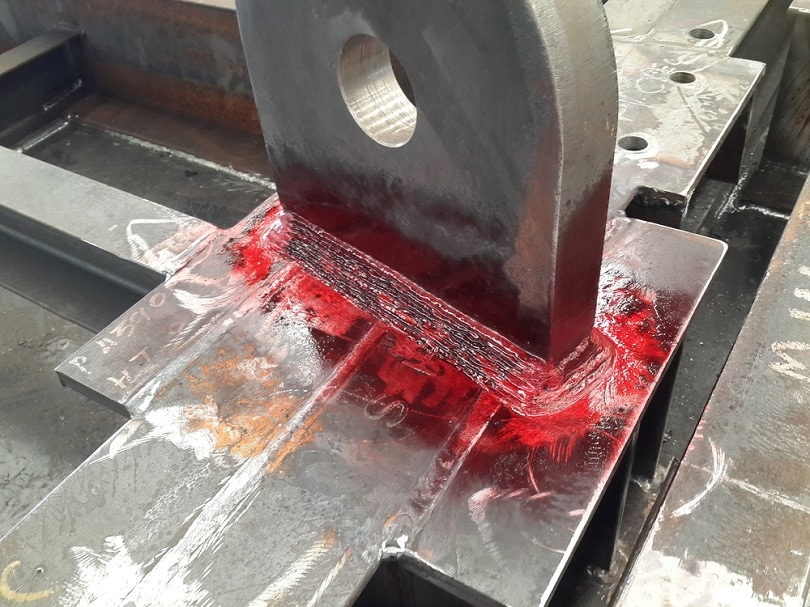

Featured image credit: Praphan Jampala, Shutterstock